Islam as a Moral and Political Ideal

- Parent Category: Prose Works

- Hits: 21557

- Print , Email

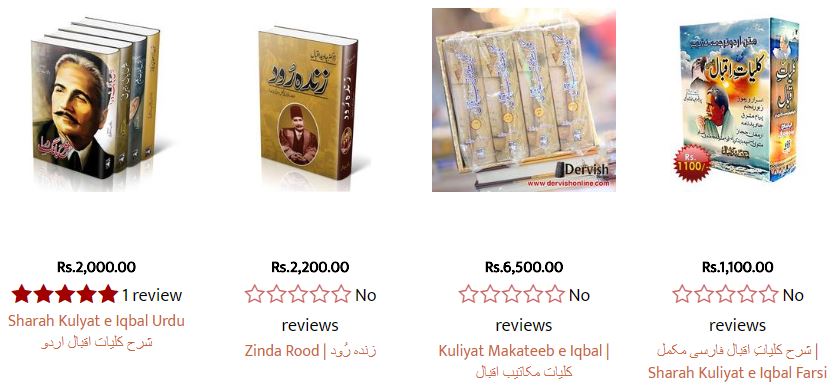

Islam as a Moral and Political Ideal*[1]

Iqbal read this paper at the anniversary celebrations of Anjuman Himayat-i-Islam on the Easter, 1909. It was subsequently published in Hindustan Review (Allahabad) in July and December the same year.

SPEECHES, WRITINGS AND STATEMENTS OF IQBAL

By

LATIF AHMAD SHERWANI

IQBAL ACADEMY PAKISTAN

EDITED AND PROOFREAD

BY

ALEENA ABAID

INTERNATIONAL IQBAL SOCIETY

There are three points of view from which a religious system can he approached: the standpoint of the teacher, that of the expounder, and that of the critical student. I do not pretend to be a teacher whose thought and action are or ought to be in perfect harmony in so far as he endeavours to work out in his own life the ideals which he places before others and thus influences his audience more by example than by precept. Nor do I claim the high office of an expounder who brings to hear a subtle intellect upon his task, endeavours to explain all the various aspects of the principles he expounds and works with certain presuppositions, the truth of which he never questions. The attitude of the mind, which characterises a critical student, is fundamentally different from that of the teacher and the expounder. He approaches the subject of his inquiry free form all presuppositions, and tries to understand the organic structure of a religious system, just as a biologist would study a form of life or a geologist a piece of mineral. His object is to apply methods of scientific research to religion, with a view to discover how the various elements in a given structure fit in with one another, how each factor functions individually, and how their relation with one another determines the functional value of the whole. He looks at the subject from the standpoint of history and raises certain fundamental questions with regard to the origin, growth, and formation of the system he proposes to understand. What are the historical forces, the operation of which evoked, as a necessary consequence, the phenomenon of a particular system? Why should a particular religious system be produced by a particular people? What is the real significance of a religious system in the history of the people who produced it, and in the history of man-kind as a whole? Are there any geographical causes, which determine the original locality of a religion? How far does it reveal the inmost soul of a people, their social, moral and political aspirations? What transformation, if any, has it worked in them? How far has it contributed towards the realisation of the ultimate purpose revealed in the history of man? These are some of the questions, which the critical student of religion endeavours to answer, in order to comprehend its structure and to estimate its ultimate worth as a civilising agency among the forces of historical evolution.

I propose to look at Islam from the standpoint of the critical student. But I may state at the outset that I avoid the use of expressions current in popular Revelation Theology; since my method is essentially scientific and consequently necessitates the use of terms which can be interpreted in the light of every-day human experience. For instance, when 1 say that the religion of a people is the sum total of their life experience finding a definite expression through the medium of a great personality, I am only translating the fact of revelation into the language of science. Similarly, interaction between individual and universal energy is only another expression for the feeling of prayer, which ought to be so described for purposes of scientific accuracy. It is because I want to approach my subject from a thoroughly human standpoint and not because I doubt the fact of Divine Revelation as the final basis of all religion that I prefer to employ expressions of a more scientific content.

Islam is moreover the youngest of all religions, the last creation of humanity. Its founder stands out clear before us; he is truly a personage of history and lends himself freely even to the most searching criticism. Ingenious legend has weaved no screens round his figure; he is born in the broad day-light of history; we can thoroughly understand the inner spring of his actions; we can subject his mind to a keen psychological analysis. Let us then for the time being eliminate the supernatural element and try to understand the structure of Islam as we find it.

I have just indicated the way in which a critical student of religion approaches his subject. Now, it is not possible for me, in the short space at my disposal, to answer, with regard to Islam, all the questions, which as a critical student of religion I ought to raise and answer in order to reveal the real meaning of this religious system. I shall not raise the question of the origin and the development of Islam. Nor shall I try to analyse the various currents of thought in the pre-Islamic Arabian society, which found a final focus in the utterances of the Prophet of Islam. I shall confine my attention to the Islamic ideal in its ethical and political aspects only.

To begin with, we have to recognise that every great religious system starts with certain propositions concerning the nature of man and the universe. The psychological implication of Buddhism, for instance, is the central fact of pain as a dominating element in the Constitution of the universe. Man, regarded as an individuality, is helpless against the forces of pain, according to the teachings of Buddhism. There is an indissoluble relation between pain and the individual consciousness which, as such, is nothing but a constant possibility of pain. Freedom from pain means freedom from individuality. Starting from the fact of pain, Buddhism is quite consistent in placing before man the ideal of self-destruction. Of the two terms of this relation, pain and the sense of personality, one (i.e. pain) is ultimate; the other is a delusion from which it is possible to emancipate ourselves by ceasing to act on those lines of activity which have a tendency to intensify the sense of personality. Salvation, then, according to Buddhism, is inaction, renunciation of self and unworldliness are the principal virtues. Similarly, Christianity, as a religious system, is based on the fact of sin. The world is regarded as evil and the taint of sin is regarded as hereditary to man, who, as an individuality, is insufficient and stands in need of some supernatural personality to intervene between him and his Creator. Christianity, unlike Buddhism, regards human personality as something real but agrees with Buddhism in holding that man as a force against sin is insufficient. There is, however, a subtle difference in the agreement. We can, according to Christianity, get rid of sin by depending upon a Redeemer; we can free ourselves from pain, according to Buddhism, by letting this insufficient force dissipate or lose itself in the universal energy of nature. Both agree in the fact of insufficiency and both agree in holding that this insufficiency is an evil; but while the one makes up the deficiency by bringing in the force of a redeeming personality, the other prescribes its gradual reduction until it is annihilated altogether.

Again, Zoroastrianism looks upon nature as a scene of endless struggle between the powers of evil and the powers of good and recognises in man the power to choose any course of action he likes. The universe, according to Zoroastrianism, is partly evil, partly good; man is neither wholly good nor wholly evil, but a combination of the two principles—light and darkness continually fighting against each other for universal supremacy. We see then that the fundamental pre-suppositions, with regard to the nature of the universe and man, in Buddhism, Christianity and Zoroastrianism respectively are the following:

- There is pain in nature and man regarded as an individual is evil (Buddhism).

- There is sin in nature and the taint of sin is fatal to man (Christianity).

- There is struggle in nature; man is a mixture of the struggling forces and is free to range himself on the side of the powers of good, which will eventually prevail (Zoroastrianism).

The question now is, what is the Muslim view of the universe and man? What is the central ideal in Islam, which determines the structure of the entire system? We know that sin, pain and sorrow are constantly mentioned in the Quran. The truth is that Islam looks upon the universe as a reality and consequently recognises as reality all that is in it. Sin, pain, sorrow, struggle are certainly real but Islam teaches that evil is not essential to the universe; the universe can be reformed; the elements of sin and evil can be gradually eliminated. All that is in the universe is God’s, and the seemingly destructive forces of nature become sources of life, if properly controlled by man, who is endowed with the power to understand and to control them.

These and other similar teachings of the Quran, combined with the Quranic recognition of the reality of sin and sorrow, indicate that the Islamic view of the universe is neither optimistic nor pessimistic. Modern psychometry has given the final answer to the psychological implications of Buddhism. Pain is not an essential factor in the constitution of the universe, and pessimism is only a product of a hostile social environment. Islam believes in the efficacy of well-directed action; hence the standpoint of Islam must he described as melioristic —the ultimate presupposition and justification of all human effort at scientific discovery and social progress. Although Islam recognises the fact of pain, — sin and struggle in nature, yet the principal fact, which stands in the way of man’s ethical progress is, according to Islam, neither pain, nor sin, nor struggle. It is fear to which man is a victim owing to his ignorance of the nature of his environment and want of absolute faith in God. The highest stage of man’s ethical progress is reached when he becomes absolutely free from fear and grief.

The central proposition, which regulates the structure of Islam then is that there is fear in nature, and the object of Islam is to free man from fear. This view of the Universe indicates also the Islamic view of the metaphysical nature of man. If fear is the force, which dominates man and counteracts his ethical progress, man must be regarded as a unit of force, an energy, a will, a germ of infinite power, the gradual unfoldment of which must be the object of all human activity. The essential nature of man, then, consists in will, not intellect or understanding.

With regard to the ethical nature of man too, the teaching of Islam is different from those of other religious systems. And when God said to the angels “I am going to make a Viceroy on the earth,” they said: “Art Thou creating one who spills blood and disturbs the peace of the earth, and we glorify Thee and sing Thy praises?” God answered? “I know what you do not know.” This verse of the Quran, read in the light of the famous tradition that every child is born a Muslim (peaceful) indicates that, according to the tenets of Islam, man is essentially good and peaceful.—a view explained and defended, in our own, times, by Rousseau—the great father of modern political thought. The opposite view, the doctrine of the depravity of man held by the Church of Rome, leads to the most pernicious religious and political consequences. Since if man is elementally wicked, he must not be permitted to have his own way: his entire life must be controlled by external authority. This means priesthood in religion and autocracy in politics. The Middle Ages in the history of Europe drove this dogma of Romanism to its political and religious consequences, and the result was a form of society which required terrible revolutions to destroy it and to upset the basic pre-suppositions of its structure. Luther, the enemy of despotism in religion, and Rousseau, the enemy of despotism in politics, must always be regarded as the emancipators of European humanity from the heavy fetters of Popedom and absolutism, and their religious and political thought must be understood as a virtual denial of the Church dogma of human depravity. The possibility of the elimination of sin and pain from the evolutionary process and faith in the natural goodness of man are the basic propositions of Islam, as of modern European civilisation, which has, almost unconsciously, recognised the truth of these propositions in spite of the religious system with which it is associated. Ethically speaking, therefore, man is naturally good and peaceful. Metaphysically speaking, he is a unit of energy, which cannot bring out its dormant possibilities owing to its misconception of the nature of its environment. The ethical ideal of Islam is to disenthral man from fear, and thus to give him a sense of his personality, to make him conscious of himself as a source of power. This idea of man as an individuality of infinite power determines, according to the teachings of Islam, the worth of all human action. That which intensifies the sense of individuality in man is good, that which enfeebles it is bad. Virtue is power, force, strength; evil is weakness. Give man a keen sense of respect for his own personality, let him move fearless and free in the immensity of God’s earth, and he will respect the personalities of others and become perfectly virtuous. It is not possible for me to show in the course of this paper how all the principal forms of vice can be reduced to fear. But we will now see the reason why certain forms of human activity, e.g. self-renunciation, poverty, slavish obedience which sometimes conceals itself under the beautiful name of humility and unworldliness—modes of activity which tend to weaken the force of human individuality—are regarded as virtues by Buddhism and Christianity, and altogether ignored by Islam. While the early Christians glorified in poverty and unworldliness, Islam looks upon poverty as a vice and says: “Do not forget thy share of the world.” The highest virtue from the standpoint of Islam is righteousness, which is defined by the Quran in the following manner:

It is not righteousness that ye turn your faces in prayers towards east and west, but righteousness is of him who believeth in God and the last day and the angels and the scriptures and the Prophets, who give the money for God’s sake unto his kindred and unto orphans and the needy and to strangers and to those who ask and for the redemption of captives; of those who are constant at prayer, and of those who perform their covenant when they have covenanted and behave themselves patiently in adversity and in times of violence. (2:177).

It is, therefore, evident that Islam, so to speak, transmutes the moral values of the ancient world, and declares the preservation, intensification of the sense of human personality, to be the ultimate ground of all ethical activity. Man is a free responsible being; he is the maker of his own destiny his salvation is his own business. There is no mediator between God and man. God is the birth right of every man. The Quran, therefore, while it looks upon Jesus Christ as the spirit of God, strongly protests against the Christian doctrine of redemption, as well as the doctrine of an infallible visible head of the Church—doctrines, which proceed upon the assumption of the insufficiency of human personality and tend to create in man a sense of dependence, which is regarded by Islam as a force obstructing the ethical progress of man. The law of Islam is almost unwilling to recognise illegitimacy, since the stigma of illegitimacy is a great blow to the healthy development of independence in man. Similarly, in order to give man an early sense of individuality the law of Islam has laid down that a child is an absolutely free human being at the age of fifteen.

To this view of Muslim ethics, however, there can be one objection. If the development of human individuality is the principal concern of Islam, why should it tolerate the institution of slavery? The idea of free labour was foreign to the economic consciousness of the ancient world. Aristotle looks upon it as a necessary factor in human society. The Prophet of Islam, being a link between the ancient and the modern world, declared the principle of equality and though, like every wise reformer, he slightly conceded to the social conditions around him in retaining the name slavery, he quietly took away the whole spirit of this institution. That slaves had equal opportunity with other Muhammadans is evidenced by the fact that some of the greatest Muslim warriors, kings, premiers, scholars and jurists were slaves. During the days of the early Caliphs slavery by purchase was quite unknown; part of public revenue was set apart for purposes of manumission, and prisoners of war were either freely dismissed or freed on the payment of ransom. Slaves were also set at liberty as a penalty for culpable homicide and in expiation of a false oath taken by mistake. The Prophet’s own treatment of slaves was extraordinarily liberal. The proud aristocratic Arab could not tolerate the social elevation of a slave even when he was manumitted. The democratic ideal of perfect equality, which had found the most uncompromising expression in the Prophet’s life, could only be brought home to an extremely aristocratic people by a very cautious handling of the situation. He brought about a marriage between an emancipated slave and a free Qureish woman, a relative of his own. This marriage was a blow to the aristocratic pride of this free Arab woman; she could not get on with her husband and the result was a divorce, which made her the more helpless, since no respectable Arab would marry the divorced wife of a slave. The ever-watchful Prophet availed himself of this situation and turned it to account in his efforts at social reform. He married the woman himself, indicating thereby that not only a slave could marry a free woman, but also a woman divorced by him could become the wife of a man no less than the greatest Prophet of God. The significance of this marriage in the history of social reform in Arabia is, indeed, great. Whether prejudice, ignorance or want of insight has blinded European critics of Islam to the real meaning of this union, it is difficult to guess.

In order to show the treatment of slaves by modern Muhammadans, I quote a passage from the English translation of the autobiography of the late Amir Abdur Rahman of Afghanistan:

For instance [says the Amir], Framurz Khan, a Chitrali slave is my most trusted Commander-in-Chief at Herat, Nazir Muhammad Safar Khan, another Chitrali slave, is the most trusted official of my Court; he keeps my seal in his hand to put to any document and to my food and diet; in short he has the full confidence of my life, as well as my kingdom is in his hands. Parwana Khan, the late Deputy Commander-in-Chief, and Jan Muhammad Khan, the late Lord of Treasury, two of the highest officials of the kingdom in their lifetime, were both of them my slaves.

The truth is that the institution of slavery is a mere name in Islam, and the idea of individuality reveals itself as a guiding principle in the entire system of Muhammadan law and ethics.

Briefly speaking, then, a strong will in a strong body is the ethical ideal of Islam. But let me stop here for a. moment and see whether we, Indian Mussalmans, are true to this ideal. Does the Indian Muslim possess a strong will in a strong body? Has he got the will to live? Has he got sufficient strength of character to oppose those forces which tend to disintegrate the social organism to which he belongs? I regret to answer my questions in the negative. The reader will understand that in the great struggle for existence it is not principally number which makes a social organism survive. Character is the ultimate equipment of man, not only in his efforts against a hostile natural environment but also in his contest with kindred competitors after a fuller, richer, ampler life. The life-force of the Indian Muhammadan, however, has become woefully enfeebled. The decay of the religious spirit, combined with other causes of a political nature over which he had no control, has developed in him a habit of self-dwarfing, a sense of dependence and, above all, that laziness of spirit which an enervated people call by the dignified name of ‘contentment’ in order to conceal their own enfeeblement. Owing to his indifferent commercial morality he fails in economic enterprise, for want of a true conception of national interest and a right appreciation of the present situation of his community among the communities of this country, he is working, in his private as well as public capacity, on lines which, I am afraid, must lead him to ruin. How often do we see that he shrinks from advocating a cause, the significance of which is truly national, simply because his standing aloof pleases an influential Hindu, through whose agency he hopes to secure a personal distinction? I unhesitatingly declare that I have greater respect for an illiterate shopkeeper, who earns his honest bread and has sufficient force in his arms to defend his wife and children in times of trouble than the brainy graduate of high culture, whose low timid voice betokens the dearth of soul in his body, who takes pride in his submissiveness, eats sparingly, complains of sleepless nights and produces unhealthy children for his community, if he does produce any at all. I hope I shall not be offending the reader when I say that I have a certain amount of admiration for the devil. By refusing to prostrate himself before Adam whom he honestly believed to be his inferior, he revealed a high sense of self-respect, a trait of character which in my opinion ought to redeem him from his spiritual deformity, just as the beautiful eyes of the toad redeem him from his physical repulsiveness. And I believe God punished him not because he refused to make himself low before the progenitor of an enfeebled humanity, but because he declined to give absolute obedience to the will of the Almighty Ruler of the Universe. The ideal of our educated young men is mostly service, and service begets, specially in a country like India, that sense of dependence which undermines the force of human individuality. The poor among us have, of course, no capital; the middle class people cannot undertake joint economic enterprise owing to mutual mistrust; and the rich look upon trade as an occupation beneath their dignity. Truly economic dependence is the prolific mother of all the various forms of vice. Even the vices of the Indian Muhammadan indicate the weakness of life-force in him. Physically too he has undergone dreadful deterioration. If one sees the pale, faded faces of Muhammadan boys in schools and colleges, one will find the painful verification of my statement. Power, energy, force, strength, yes physical strength, is the law of life. A strong man may rob others when he has got nothing in his own pocket; but a feeble person, he must die the death of a mean thing in the world’s awful scene of continual warfare. But how [to] improve this undesirable state of things?

Education, we are told, will work the required transformation. I may say at once that I do not put much .faith in education as a means of ethical training—I mean education as understood in this country. The ethical training of humanity is really the work of great personalities, who appear time to time during the course of human history. Unfortunately our present social environment is not favourable to the birth and growth of such personalities of ethical magnetism. An attempt to discover the reason of this dearth of personalities among us will necessitate a subtle analysis of all the visible and invisible forces which are now determining the course of our social evolution—an enquiry which I cannot undertake in this paper. But all unbiased persons will easily admit that such personalities are now rare among us. This being the case, education is the only thing to fall back upon. But what sort of education? There is no absolute truth in education, as there is none in philosophy or science. Knowledge for the sake of knowledge is a maxim of fools. Do we ever find a person rolling in his mind the undulatory theory of light simply because it is a fact of science? Education, like other things, ought to be determined by the needs of the learner. A form of education which has no direct bearing on the particular type of character which you want to develop is absolutely worthless. I grant that the present system of education in India gives us bread and butter. We manufacture a number of graduates and then we have to send titled mendicants to Government to beg appointments for them. Well, if we succeed in securing a few appointments in the higher branches of service, what then? It is the masses who constitute the backbone of the nation; they ought to be better fed, better housed and properly educated. Life is not bread and butter alone; it is something more; it is a healthy character reflecting the national ideal in all its aspects. And for a truly national character, you ought to have a truly national education. Can you expect free Muslim character in a young boy who is brought up in an aided school and in complete ignorance of his social and historical tradition? You administer to him doses of Cromwell’s history; it is idle to expect that he will turn out a truly Muslim character. The knowledge of Cromwell’s history will certainly create in him a great deal of admiration for the Puritan revolutionary; but it cannot create that healthy pride in his soul which is the very lifeblood of a truly national character. Our educated young man knows all about Wellington and Gladstone, Voltaire and Luther. He will tell you that Lord Roberts worked in the South African War like a common soldier at the age of eighty; but how many of us know that Muhammad II conquered Constantinople at the age of twenty-two? How many of us have even the faintest notion of the influence of our Muslim civilisation over the civilisation of modern Europe? How many of us are familiar with the wonderful historical productions of Ibn Khaldun or the extraordinarily noble character of the great Mir Abdul Qadir of Algeria? A living nation is living because it never forgets its dead. I venture to say that the present system of education in this country is not at all suited to us as a people. It is not true to our genius as a nation, it tends to produce an un-Muslim type of character, it is not determined by our national requirements, it breaks entirely with our past and appears to proceed on the false assumption that the idea of education is the training of human intellect rather than human will. Nor is this superficial system true to the genius of the Hindus. Among them, it appears to have produced a number of political idealists, whose false reading of history drives them to the upsetting of all conditions of political order and social peace. We spend an immense amount of money every year on the education of our children. Well, thanks to the King-Emperor, India is a free country; everybody is free to entertain any opinion he likes—I look upon it as a waste. In order to be truly ourselves, we ought to have our own schools, our own colleges, and our own universities, keeping alive our social and historical tradition, making us good and peaceful citizens and creating in us that free but law-abiding spirit which evolves out of itself the noblest types of political virtue. I am quite sensible of the difficulties that lie in our way, all that I can say is that if we cannot get over our difficulties, the world will soon get rid of us.

Having discussed in the last issue of this Review the ethical ideals of Islam I now proceed to say a few words on the political aspect of the Islamic ideal. Before, however, I come to the subject I wish to meet an objection against Islam so often brought forward by our European critics. It has been said that Islam is a religion which implies a state of war and can thrive only in a state of war. Now there can be no denying that war is an expression of the energy of a nation; a nation which cannot fight cannot hold its own in the strain and stress of selective competition which constitutes an indispensable condition of all human progress. Defensive war is certainly permitted by the Quran; but the doctrine of aggressive war against unbelievers is wholly unauthorised by the Holy Book of Islam. Here are the words of the Quran:

Summon them to the way of thy Lord with wisdom and kindly warning, dispute them in the kindest manner. Say to those who have been given the book and to the ignorant: Do you accept Islam? Then, if they accept Islam they are guided aright; but if they turn away then thy duty is only preaching; and God’s eye is on His servants.

All the wars undertaken during the lifetime of the Prophet were defensive. His war against the Roman Empire in 628 A.D. began by a fatal breach of international law on the part of the Government at Constantinople who killed the innocent Arab envoy sent to their Court. Even in defensive wars he forbids wanton cruelty to the vanquished. I quote here the touching words which he addresses to his followers when they were starting for a fight:

In avenging the injuries inflicted upon us, disturb not the harmless votaries of domestic seclusion, spare the weakness of the female sex, injure not the infant at the breast, or those who are ill in bed. Abstain from demolishing the dwellings of the unresisting inhabitants, destroy not the means of their subsistence, nor their fruit trees, and touch not the palm.

The history of Islam tells us that the expansion of Islam as a religion is in no way related to the political power of its followers. The greatest spiritual conquests of Islam were made during the days of our political decrepitude. When the rude barbarians of Mongolia drowned in blood the civilisation of Baghdad in 1258 A.D., when the Muslim power fell in Spain and the followers of Islam were mercilessly killed or driven out of Cordova by Ferdinand in 1236, Islam had just secured a footing in Sumatra and was about to work the peaceful conversion of the Malay Archipelago.

In the hours of its political degradation [says Professor Arnold], Islam has achieved some of its most brilliant conquests. On two great historical occasions, infidel barbarians have set their foot on the necks of the followers of the Prophet, the Seljuk Turks in the eleventh and the Mongols in the thirteenth century, and in each case the conquerors have accepted the religion of the conquered.

We undoubtedly find [says the same learned scholar elsewhere] that Islam gained its greatest and most lasting missionary triumph in times and places in which its political power has been weakest, as in South India and Eastern Bengal.

The truth is that Islam is essentially a religion of peace. All forms of political and social disturbance are condemned by the Quran in the most uncompromising terms. I quote a few verses from the Quran:

Eat and drink from what God has given you and run not on face of the earth in the matter of rebels.

And disturb not the peace of the earth after it has been reformed; this is good for you if you are believers.

And do good to others as God has done good to thee, and seek not the violation of peace in the earth, for God does not love those who break the peace.

That is the home in the next world, which we build for those who do not mean rebellion and disturbance in the earth, and the end is for those who fear God.

Those who rebelled in cities and enhanced disorder in them, God visited them with His whip of punishment.

One sees from these verses how severely all forms of political and social disorder are denounced by the Quran. But the Quran is not satisfied with mere denunciation of the evil of fesad. It goes to the very root of this evil. We know that both in ancient and modern times, secret meetings have been a constant source of political and social unrest. Here is what the Quran says about such conferences: “O believers, if you converse secretly—that is to say, hold secret conference, converse not for purpose of sin and rebellion.” The ideal of Islam is to secure social peace at any cost. All methods of violent change in society are condemned in the most unmistakable language. Tartushi—a Muslim lawyer of Spain—is quite true to the spirit of Islam when he says: “Forty years of tyranny are better than one hour of anarchy.” “Listen to him and obey him,” says the Prophet of God in a tradition mentioned by Bukharee, “even if a negro slave is appointed to rule over you.” Muslim mentioned another important tradition of the Prophet on the authority of Arfaja, who says: “I heard the Prophet of God say, when you have agreed to follow one man then if another man comes forward intending to break your stick (weaken your strength) or to make you disperse in disunion, kill him.”

Those among us who make it their business to differ from the general body of Mussalmans in political views ought to read this tradition carefully, and if they have any respect for the words of the Prophet, it is their duty to dissuade themselves from this mean traffic in political opinion, which though perhaps it brings a little personal gain to them, is exceedingly harmful to the interests of the community. My object, in citing these verses and traditions, is to educate political opinion on strictly Islamic lines. In this country, we are living under a Christian Government. We must always keep before our eyes the example of those early Muhammadans who, persecuted by their own countrymen, had to leave their home and to settle in the Christian State of Abyssinia. How they behaved in that land must be our guiding principle in this country where an overdose of Western ideas has taught people to criticise the existing Government with a dangerous lack of historical perspective. And our relations with the Christians are determined for us by the Quran, which says:

And thou wilt find nearer to the friendship of the believers those men who call themselves Christians. This is because among them there are learned men and hermits, and they are never vain.

Having thus established that Islam is a religion of peace, I now proceed to consider the purely political aspect of the lslamic ideal—the ideal of Islam as entertained by a corporate individuality. Given a settled society, what does Islam expect from its followers regarded as a community? What principles ought to guide them in the management of communal affairs? What must be their ultimate object and how is it to be achieved? We know that Islam is something more than a creed, it is also a community, a nation. The membership of Islam as a community is not determined by birth, locality or naturalisation; it consists in the identity of belief. The expression Indian Muhammadan, however convenient it may be, is a contradiction in terms: since Islam in its essence is above all conditions of time and space. Nationality with us is a pure idea; it has no geographical basis. But inasmuch as the average man demands a material centre of nationality, the Muslim looks for it in the holy town of Mecca, so that the basis of Muslim nationality combines the real and the ideal, the concrete and the abstract. When, therefore, it is said that the interests of Islam are superior to those of the Muslim, it is meant that the interests of the individual as a unit are subordinate to the interests of the community as an external symbol of the Islamic principle. This is the only principle, which limits the liberty of the individual, who is otherwise absolutely free. The best form of Government for such a community would be democracy, the ideal of which is to let man develop all the possibilities of his nature by allowing him as much freedom as practicable. The Caliph of Islam is not an infallible being; like other Muslims he is subject to the same law; he is elected by the people and is disposed by them if he goes contrary to the law. An ancestor of the present Sultan of Turkey was sued in an ordinary law court by a mason, who succeeded in getting him fined by the town Qazee. Democracy, then, is the most important aspect of Islam regarded as a political ideal. It must however be confessed that the Muslims, with their ideal of individual freedom, could do nothing for the political improvement of Asia. Their democracy lasted only thirty years and disappeared with their political expansion. Though the principle of election was not quite original in Asia (since the ancient Parthian Government was based on the same principle), yet somehow or other it was not suited to the nations of Asia in the early days of Islam. It was, however, reserved for a Western nation politically to vitalise the countries of Asia. Democracy has been the great mission of England in modern times and English statesmen have boldly carried this principle to countries which have been, for centuries, groaning under the most atrocious forms of despotism. The British Empire is a vast political organism, the vitality of which consists in the gradual working out of this principle. The permanence of the British Empire as a civilising factor in the political evolution of mankind is one of our greatest interests. This vast Empire has our fullest sympathy and respect since it is one aspect of our political ideal that is being slowly worked out in it. England, in fact, is doing one of our own great duties, which unfavourable circumstances did not permit us to perform. It is not the number of Muhammadans, which it protects, but the spirit of the British Empire that makes it the greatest Muhammadan Empire in the world.

To return now to the political constitution of the Muslim society. Just as there are two haste propositions underlying Muslim ethics, so there are two basic propositions underlying Muslim political constitution:

(1) The law of God is absolutely supreme. Authority, except as an interpreter of the law, has no place in the social structure of Islam. We regard it as inimical to the unfoldment of human individuality. The Shi’ias, of course, differ from the Sunnis in this respect. They hold that the Caliph or Imam is appointed by God and his interpretation of the Law is final; he is infallible and his authority, therefore, is absolutely supreme. There is certainly a grain of truth in this view; since the principle of absolute authority has functioned usefully in the course of the history of mankind. But it must be admitted that the idea works well in the case of primitive societies and reveals its deficiency when applied to higher stages of civilisation. Peoples grow out of it, as recent events have revealed in Persia, which is a Shi’a country, yet demand a fundamental structural change in her Government in the introduction of the principle of election.

(2) The absolute equality of all the members of the community. There is no aristocracy in Islam. “The noblest among you,” says the Prophet, “are those who fear God most,” There is no privileged class, no priesthood, no caste system. Islam is a unity in which there is no distinction, and this unity is secured by making men believe in the two simple propositions—the unity of God and the mission of the Prophet—propositions which are certainly of a supernatural character but which, based as they are on the general religious experience of mankind, are intensely true to the average human nature. Now, this principle of the equality of all believers made early Mussalmans the greatest political power in the world. Islam worked as a levelling force; it gave the individual a sense of his inward power; it elevated those who were socially low. The elevation of the down-trodden was the chief secret of the Muslim political power in India. The result of the British rule in this country has been exactly the same; and if England continues true to this principle it will ever remain a source of strength to her as it was to her predecessors.

But are we Indian Mussalmans true to this principle in our social economy? Is the organic unity of Islam intact in this land? Religious adventurers set up different sects and fraternities, ever quarrelling with one another; and then there are castes and sub-castes like the Hindus’. Surely we have out-Hindued the Hindu himself; we are suffering from a double caste system—the religious caste system, sectarianism, and the social caste system, which we have either learned or inherited from the Hindus. This is one of the quiet ways in which conquered nations’ revenge themselves on their conquerors. I condemn this accursed religious and social sectarianism; I condemn it in the name of God, in the name of humanity, in the name of Moses, in the name of Jesus Christ, and in the name of him—a thrill of emotion passes through the very fibre of my soul when I think of that exalted name—yes, in the name of him who brought the final message of freedom and equality to mankind. Islam is one and indivisible; it brooks no distinctions in it. There are no Wahabies, Sh’ias, Mirzais or Sunnies in Islam. Fight not for the interpretations of the truth, when the truth itself is in danger. It is foolish to complain of stumbling when you walk in the darkness of night. Let all come forward and contribute their respective shares in the great toll of the nation. Let the idols of class distinctions and sectarianism be smashed for ever; let the Mussalmans of the country be once more united into a great vital whole. How can we, in the presence of violent internal dispute, expect to succeed in persuading others to our way of thinking? The work of freeing humanity from superstition—the ultimate ideal of Islam as a community, for the realisation of which we have done so little in this great land of myth and superstition will ever remain undone if the emancipators themselves are becoming gradually enchained in the very fetters from which it is their mission to set others free.